Reflections on Covid-19: Exploring remote democratic decision making

This post looks at how the UK social landscape has been shaped by COVID-19 and especially government, healthcare and communities. Our focus is to share insights and tools that people can take away to help address their own challenges.

This post looks at how the UK social landscape has been shaped by COVID-19 and especially government, healthcare and communities. Our focus is to share insights and tools that people can take away to help address their own challenges.

At Snook, one of our missions is to work toward a kinder and smarter next era of government, and so we have an immediate interest in current shifts in how public services work. Some of these services are new and very visible, like financial support mechanisms for people and organisations in crisis, or contact-tracing initiatives.

Others, however, might be less visible, but ultimately represent longer-term changes in the relationship between government and the public.

In this post, we’ll share insights that we’ve gained from developing a tool that enables local councils to run official meetings online – an example of how everyday processes of democratic decision making are being forced to change by the crisis, and what long-term impacts might result.

The democratic process, live from the kitchen table

Before the pandemic only about 12% of the UK workforce regularly worked from home, with less than 30% having ever worked from home, so relatively few people or organisations had systems in place for staff to work from home. While it attracts little mainstream attention, how best to work from home takes on a different significance when it includes core parts of our democratic process.

In the UK, local government meetings are involved in granting permits, licenses, and planning permission, as well as allocating resources and budgets in their area; and a pandemic has meant local governments needing to find ways to hold such meetings online.

Defining a service that would meet the legal requirements of a democratic process in a virtual space is more complex than it might first appear. From the second week of the lockdown, Liam Hinshelwood and Liv Comberti from the Snook team began to work with Neil Terry and Chris Cadman-Dando from Adur & Worthing Councils (A&W) to do so. We wanted to describe some of their insights from the development process, and launch a set of reflections for further conversations.

How do meetings work in physical versus virtual space?

The meeting script. Council meetings run to a tight script. Adhering to an agreed structure is what makes these meetings legally binding. Although some functions of a meeting could be done in writing rather than in person, this would remove the opportunity for everyone to express their opinion as easily, make ‘responding’ in real time more difficult, and limit public participation. Finding ways to take the script online is preferable.

The physical space. Council meetings tend to occur in purpose-built chambers. These spaces are usually organised around a hierarchy, with the person chairing the meeting and their deputies in the centre, and the legal officer seated nearby to offer guidance where necessary. Those who will present, and those who are eligible to vote on arguments, are arranged around them. This makes it easy to see who is guiding the process.

The virtual space. All this changes in a virtual context. Here, everyone is ‘on the same level’. The performative characteristics of space have changed, and adjustments to behaviour are

necessary – people talk over each other, need to remember to mute microphones, and we also tend to see more casual dress and participants’ homes in the background. The whole atmosphere changes.

The need for rapid adaptation from a built for purpose physical space to working from home is not limited to the UK. Left: An image of the empty Hackney Town Hall, UK. Right: A recent council meeting in Clinton, USA

What are the practical problems and solutions of moving council meetings online?

Who is responsible for tech and training? Currently, there is no dedicated software to conduct either council or any other democratic meetings. Software decisions usually fall to the IT department, however, because of the urgency of moving online, the responsibility for these decisions fell to the Democratic Services Support Team at A&W. They found a need to train councillors and members of the public who were due to participate in how to use the video conferencing software and digital devices to participate in virtual meetings. Chris says “In some cases, councillors have had comparatively low exposure to modern digital technology, and it is essential that we make sure the training they receive in the necessary applications allows their other, more traditional skills (debate, scrutiny and decision making), to shine through”. Training 70 councillors was, in itself, very resource-intensive – imagine what it would be like to train hundreds at larger councils.

Scale and roles have an impact. Council meetings are of different sizes, depending on location and even the subject under discussion. For example, A&W meetings are often 30-60 people, which is relatively small and can work on a call. However, for some other councils these meetings can be much larger (e.g. Birmingham Council with around 300 councillors). As Neil from A&W observes: “In a remote context you can easily control a planning committee of 8 participants, but as the numbers increase, so do the challenges, exponentially.” The roles needed in a virtual context will be, to a degree, highly connected with their scale – facilitating a call with 20 people is not the same as facilitating one with 200+!

New roles. “There’s a need for new roles and new responsibilities in these virtual council meetings,” Liv from Snook says, “and we are only just beginning to understand what these are ”. As Chris describes: “We have identified new technical roles that we would not normally have to consider at traditional meetings. This has meant that we have had to identify additional resources outside of our small Democratic Services Support Team, and train and prepare those people we bring in. In addition to this, traditional roles such as that of the chairman now require different skills and knowledge which has been challenging.”

Trade-offs between software and protocol. Most council constitutions require public visibility on how each councillor has voted. In A&W, this is done by councillors verbally confirming their vote. However, in larger councils, registering hundreds of verbal votes one at a time is impractical. The processes councils follow and the tasks required are tied in with the platforms they are using.

Infrastructure limitations. Designing around participants’ internet connectivity is a huge challenge. At best it can mean councillors being forced to abstain from voting on issues where they haven’t heard the full debate. The risk increases when the chair or legal counsel’s connection drops. And that’s clearly not the worst that can happen.

How can we enable the public to take part – and given that digital inclusiveness is always a problem, what new challenges might arise?

Technology shifts who is being included and excluded. Liv explains: “Physical meetings may exclude parents, disabled people, or simply those living busy lives. Virtual meetings are more likely to exclude older generations or those without access to the technology needed. But overall, virtual meetings may actually be more accessible.”

A less intimidating prospect. Members of the public can now see both the meeting and what participation involves much more easily than they could before. The formality and pomp of physical meetings disappears, making them more approachable and open to all.

How can issues like these be addressed?

The biggest challenge the Snook team found was not the ability of a council team to systematically come up with a solution to every issue outlined above – something they excelled at. It was the sheer amount to think about, and the risk of overlooking or not anticipating something that turned out to be critical. As Chris points out: “In some cases we have protocols for dealing with issues and we can adapt them to the online context. However, there are challenges that you would never ever think about.” Some councils have been discovering these the hard way. This means greater demands on council resources in a time where they are already considerably overstretched.

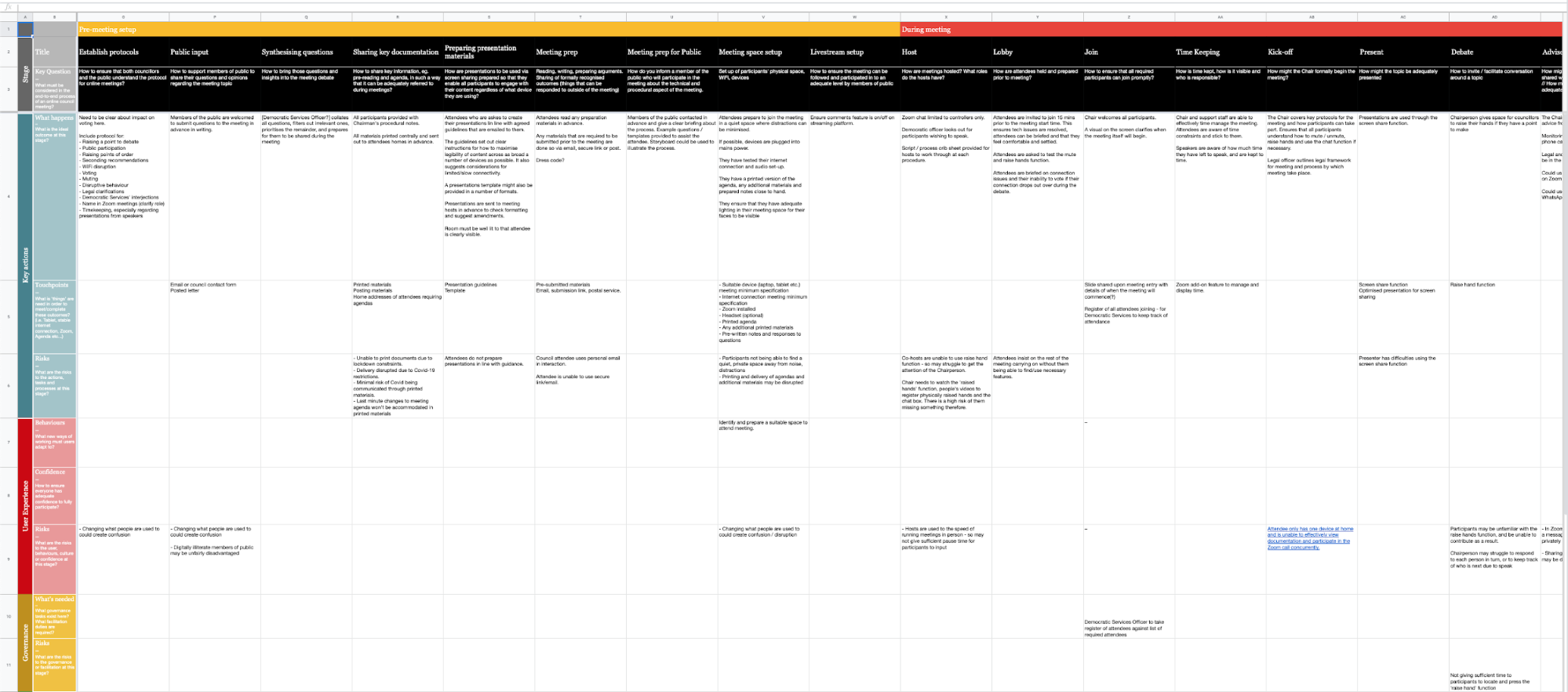

A new tool. With this in mind, we worked with the A&W team to create an extensive blueprint of every stage of the process – from meeting set-up through post-meeting admin – in granular detail. At every stage, the team considered behaviours, hardware, software, governance, and legislative risks. “They shared that what they found incredibly helpful about that”, Liv says, “was that it ensured there was nothing they hadn’t thought about – it was a very comprehensive lens. It wasn’t about putting something in each cell – in a way the blueprint acted as a checklist for them to make sure they’d thought about everything and proposed solutions”.

A&W Remote Council Meetings Blueprint

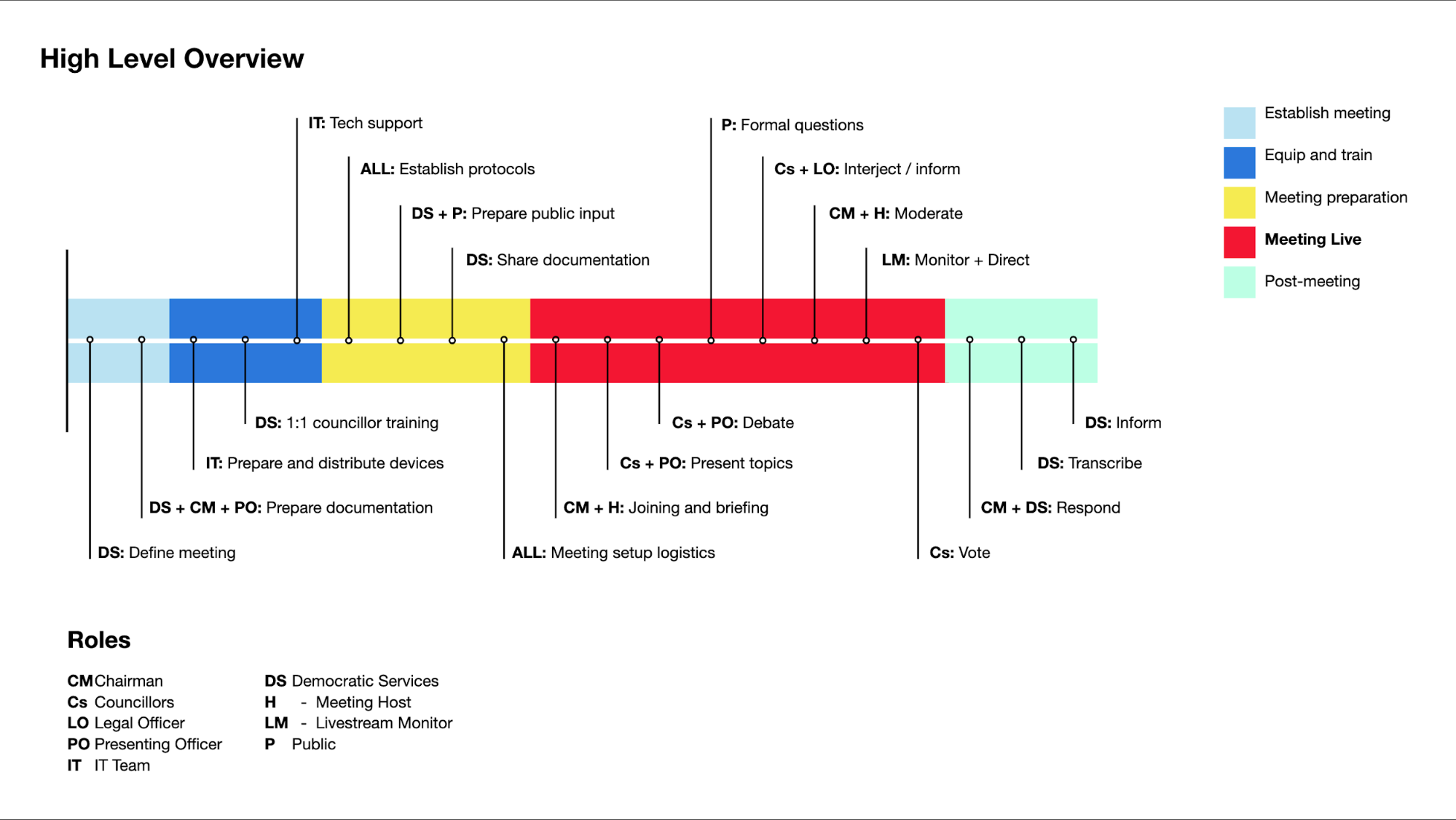

A user manual for governance. Ultimately, a blueprint is a difficult thing to follow, and not every participant needs to know the whole process. Liv told us, “We need a big picture of the whole process, broken down into the different roles required, so that people can see where their role fits in, including members of the public. What we really need to exist is a user manual for each member of a council meeting”.

Sketch of A&W remote council meeting process by roles

Local variation. Such a blueprint would be different for individual councils. “ While there is a centralised Local Government Act 2000 that outlines a strong common framework for what should and shouldn’t be done, implementation is different at a local level. They are currently changing the governance to reflect the current situation”, Liam says.

At Snook, we are deeply interested in understanding what kind of long-term impact will result from these changes and interventions. While it’s likely that many councils will move back towards physical meetings, there are aspects of online provision that we would like to see pursued, especially its ability to make meetings more approachable and accessible. We see digital not just as a lever to transform delivery channels, but as a creator of new activities and roles which will shape what governance will look like around the world.

As Neil puts it: “Whilst the current legislation allowing remote meetings is only in place until next year, we’re planning on some form of remote participation being here to stay. Before the lockdown, we had pressures from those who welcomed remote participation and those who opposed it. In demonstrating what is possible, the opposition has dropped and we’re in the process of shaping the new normal”.

We’d like to thank Adur and Worthing Council for involving us in this interesting piece of work, and Benedict and Marta from Rival for partnering with us on the research for this post. If you’d like to get involved in discussing redesign of democratic processes for inclusion and accessibility in the digital age, please get in touch.