Thinking in systems to address the climate crisis

Luca Piallini is a Service Designer at Snook, focused on our thriving planet mission. In this blog, he explores how we can use systems thinking to navigate the complexity of the climate crisis. He considers how we can understand underlying patterns, leverage impact and so create a more sustainable future.

Luca Piallini is a Service Designer at Snook, focused on our thriving planet mission. In this blog, he explores how we can use systems thinking to navigate the complexity of the climate crisis. He considers how we can understand underlying patterns, leverage impact and so create a more sustainable future.

On December 24, 1968, Apollo 8 mission photographer William Anders took a picture that would change humanity. The photo – titled “Earthrise” – was not just a testimony of the powerful technological progress that enabled photography or space exploration. It provoked a deep shift in perception.

For the first time in history, we could see our planet in its entirety. A living system called nature, exchanging energy with the universe and creating the perfect conditions for other systems to flourish within it.

Only forty years later, our collective conscience had to come to terms with another, much more dramatic realisation: its fragility.

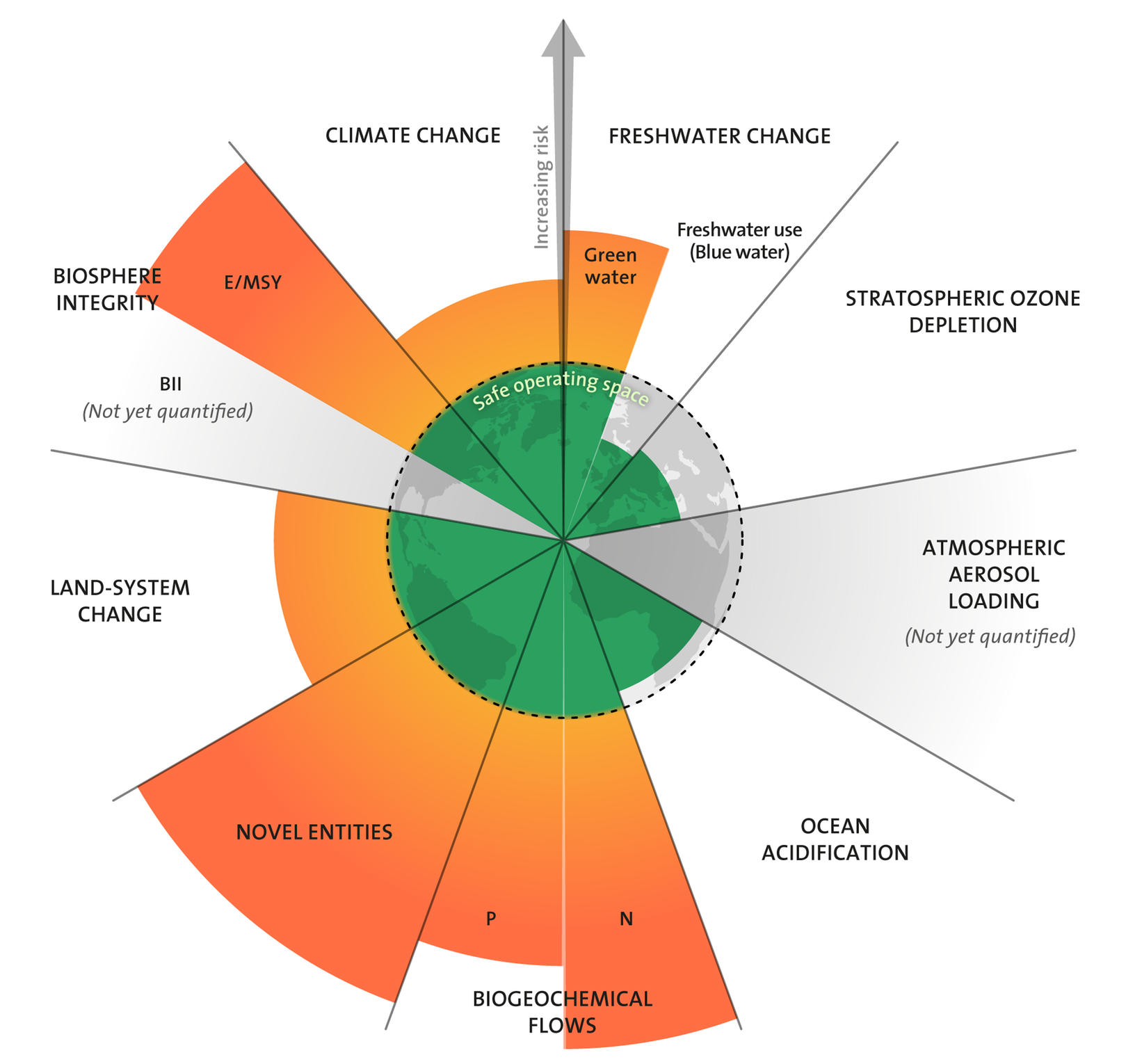

The research led by Johan Rockström and his colleagues at Stockholm Resilience Centre – further popularised by the 2021 Netflix documentary Breaking Boundaries: The Science of our Planet – revealed exactly how humanity’s increasing pressure on the natural world is leading us towards irreversible tipping points. Our living system’s delicate and dynamic balance is at stake.

Early data shows this year’s temperatures are hitting new record highs, setting our planet to breach the +1.5 degrees threshold as early as 2027 and propelling extensive wildfires, large-scale migrations and unprecedented droughts which some consider to be the next pandemic. New precipitation patterns, new healthcare risks, new global migrations. It’s all connected.

Unfortunately, as Force of Nature founder and youth climate activist Clover Hogan puts it: “our actions alone won’t solve the climate crisis.” It’s time we talk about systemic change, and how do people take part in it.

“It’s not scary to talk about systemic change. It is scary to pretend there’s hope in another 10 years of incrementalism.”

– Clover Hogan

Image Credit: J. Lokrantz/Azote based on Steffen et al. 2015.

The world around us

Nature, society, technology are all huge systems. They’re so embedded in our lives we often overlook them and so intricate we don’t fully grasp how they work. But if we don’t understand and steer them, they can become more difficult to manage, unknowingly guiding our society towards unsustainable futures.

Where other tools fail, systems thinking provides an invaluable methodology which can unlock ways to address the most important issues of our time by:

- Understanding the complexity of wicked problems

- Identifying leverage points to unlock positive impact

- Addressing unintended consequences

Let’s take a deep dive into each of these areas.

Understanding the Complexity of Wicked Problems

Poverty, migrations, pandemics and climate change are also systems. Academia calls them ‘wicked problems’. For me, these ‘hard’ problems are the best expression of VUCA, a popular acronym that is short for Volatility, Uncertainty, Complexity, and Ambiguity.

They are complex: they exist at multiple levels of scale and involve a multitude of elements which are deeply interconnected and interdependent. They are the product of spontaneous interactions and display emerging properties, which means their responses are highly volatile and unpredictable. They are ambiguous and difficult to frame because they straddle sectorial, organisational and disciplinary boundaries. Finally, they are uncertain because they don’t have a clear solution.

Whether we like it or not, all of us are effectively designing for and within these systems. Yet, when working with systems, we operate at a scale where the rules are literally turned upside down, which is making our job a lot harder.

The aim of the work no longer is fixing individual problems, but rather improving the system because problems are too large and entrenched for traditional solutions to address them in their entirety.

The approach is also different: we go from chasing problems to understanding the underlying patterns and dynamics that underpin them.

Old mindsets are leading to ineffective solutions that end up addressing the ‘symptoms’ of a bigger, higher-level problem, rather than its root causes. While traditional UCD works at a microscopic scale, we need to find ways to integrate a telescopic lens that looks at the bigger picture.

We’ve been adopting this mindset into our practice for many years. Snook co-founder and Director at the School of Good Services Sarah Drummond calls it a ‘full stack’ approach.

Looking at the climate crisis through a system thinking lens offers a tragic example of how pursuing individual directions can be problematic.

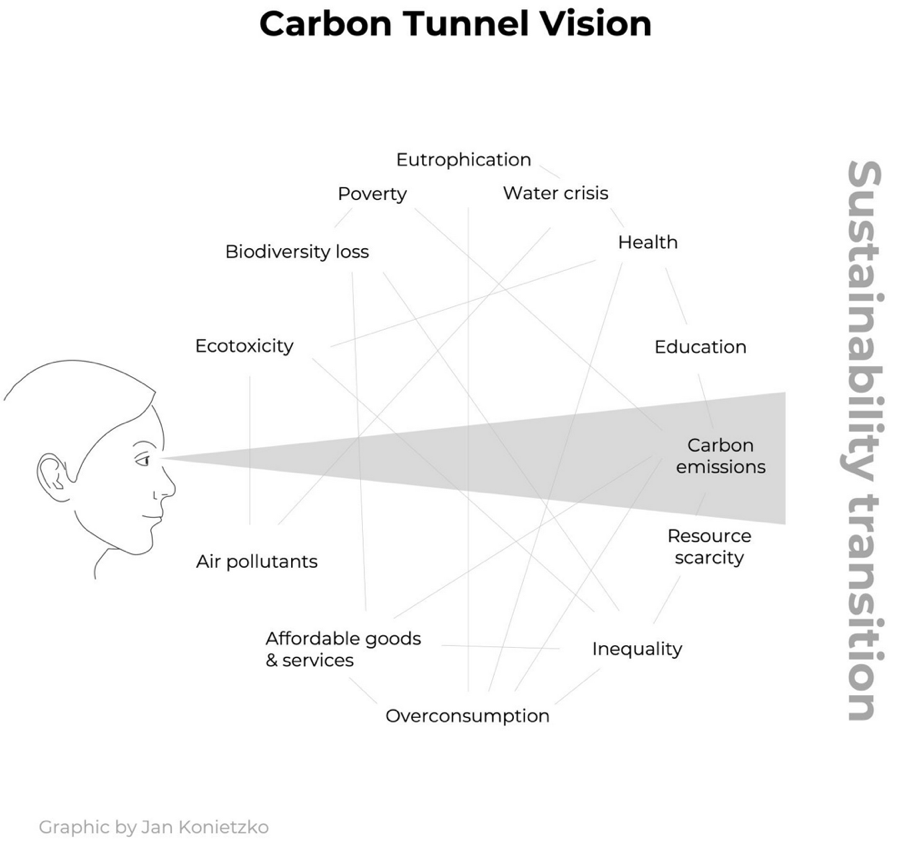

This is captured in a recent illustration by Maastricht Sustainability Institute’s Jan Konietzko which emphasises the interconnectedness of Earth’s systems.

Image Credit: Jan Konietzko (2022)

Focusing exclusively on ‘Net Zero’ strategies (e.g. tree planting, renewables) in a desperate attempt to curb emissions may inadvertently exacerbate or neglect other pressing issues, resulting in negative effects on the whole system.

For example, a larger supply chain may result in an increase in emissions. Large-scale solar or wind farms could destroy habitats or disrupt wildlife populations. Finally, the cost of new technologies may disproportionately impact low-income communities, deepening existing inequalities.

It is not a coincidence that both the work of Johan Rockström and Jan Konietzko features extensive graphical illustrations of their systems. When dealing with complexity, instead of spending time understanding issues to visualise them, we do the opposite: we visualise things to understand them better. Besides helping us find structure in chaos, maps also become a shared language to spark discussion with stakeholders to refine understanding and create alignment.

Identifying Leverage Points to Unlock Positive Impact

Unlike traditional approaches that seek broad solutions, systems thinking requires an approach that is similar to acupuncture. In this ancient practice, small and precise interventions at specific points can stimulate positive change throughout the body. Similarly, designers can identify key nodes within a complex system and focus their efforts on those areas to unlock transformative change.

While they may appear chaotic, at a smaller scale, systems obey relatively simple rules, such as feedback loops. Only after identifying these dynamics can we begin to understand the areas of the system on which to focus targeted interventions.

What happened during the UK’s recent heatwave is a prime example of a reinforcing feedback loop. The intense heat prompted people to rely heavily on air conditioning, which in turn put more strain on the electricity grid. To meet this growing demand, the National Grid resorted to firing up a coal plant, which now contributes to further greenhouse gas emissions, exacerbating climate change.

In this case, designers can focus on identifying interventions that disrupt or redirect that loop to achieve desired outcomes.

Similarly, if a balancing loop is impeding progress or creating undesired stability, designers can identify interventions that shift the balance towards a more desired state (we will cover more about preferred states in a future article on Futures Thinking).

Addressing Unintended Consequences

Systems thinking also encourages designers to frame complex problems within larger timescales.

After examining the evolution of the problem (past), understanding the dynamics that govern the system (present), designers can speculate about the future and identify the unintended consequences that may emerge from their interventions.

A study conducted in Kiribati, an island nation in the central Pacific, reveals that subsidizing the coconut oil industry to discourage overfishing resulted in an unintended consequence: an increase in fishing activity. The research found that higher incomes from coconut agriculture led people to work less and spend their newfound leisure time fishing, causing a 33% rise in fishing and a 17% decline in the reef fish population.

This story also emphasises the need for decision-makers to be adaptable as opposed to anchored to plans, as wicked problems require long-term evaluation and flexible strategies. In the case of Kiribati, the government has tried to mitigate the unintended consequences by exploring the possibility of employing fishermen to patrol newly established marine protected areas as a means of creating new jobs on the water and addressing the problem of overfishing.

Looking ahead

As we navigate the challenges of an increasingly interconnected world, systems thinking provides a pathway to understanding and addressing the intricate dynamics that shape our living system. By adopting new mindsets and borrowing useful tools, we can unlock new perspectives, renew the ethical commitment of our practice and do our part to safeguard the delicate balance of our world for future generations.

Are you a design professional using systems thinking to create impact in your work?

Snook wants to hear from you! We’re always on the lookout for innovative ideas and approaches to create positive change and help people and planet thrive in balance. We believe in the power of collaboration and sharing our knowledge openly, so we can all learn from each other.

If you’ve got something to share, we invite you to use the comment section below to drop a link to a study, shout about a blog you’ve read or simply that tell us what you’ve done and what you’ve learnt.

Would you like to learn more about systems thinking?

At Snook, we are committed to designing for people and planet. That’s why we have designed a practical course delivered remotely over two half days called “User Centred Systems Thinking”. It’s a space to learn how to apply a user-centred approach to systems thinking and develop an understanding of how to address complex problems and deliver holistic solutions.

Learn more and book your place on the next User Centred Systems Thinking course.

This blog is part of a new series ‘6 core skills to design for people and planet’ where Snook shares the core skills we are weaving into our design process to support the transition to a more sustainable future.

Follow the links below to read other published articles in the series:

Stay updated on Snook thinking and practice by subscribing to our newsletter or follow us on social media – LinkedIn, Twitter, Instagram and Facebook.